Boarders

For many years in New York, Donatus Buongiorno and his wife took boarders into their home—other Italian immigrant men, both married (men whose families had not yet joined them in the U.S.) and single.

It was common among immigrants that the men emigrated before their wives and children, and that they might live with another family before securing their own housing.

The woman of the boarder household provided cooked meals and laundry service in exchange for rent from her boarders, so this was a form of home-based work whereby women contributed to a family's income, often substantially.

Through the U.S. Census, New York City directories and my grandfather's memoir, I know of seven boarders whom Donato Buongiorno and Teresa Lagata hosted from 1900 (and probably earlier) through 1919. Most, perhaps all, were relatives.

Pasquale Sannino

Buongiorno’s longest-term boarder was Pasquale Sannino, who lived with the family for several decades, including in 1907 when my grandfather’s family (his 52-year old father plus three teenaged boys) joined the household. In his memoir, my grandfather, Domenic Troisi, described Sannino as Buongiorno’s “life-long friend.”

From census reports and listings in city directories, I have confirmed that Sannino lived with the Buongiornos the entire time Buongiorno lived in New York (except for Buongiorno’s first few years before his wife arrived, when he shared apartments with other artists), first on East 12th Street in Manhattan and later in the Bronx.

After Donatus and his son Biagio Buongiorno returned to Italy in 1919, Sannino lived by himself in Manhattan.

Sannino may also have also been a family member. In the 1900 U.S. Census (where he is misidentified as "Pascal"), he is reported as Donatus Buongiorno’s cousin, but Italians use “cousin” loosely to identify any distant relative and even very close friends who are not blood relatives, so I am not sure that information is reliable. Also, I have been told by other researchers that census enumerators weren't that precise—that they sometimes stood in the stairwell of a tenement building, shouted up the stairs, “Who lives here?”, and took information from anyone who replied.

Sannino was born in 1868 in Resina (now known as Ercolano), Italy, a small town on the slopes of Mt. Vesuvius outside Naples. I suspect Buongiorno met Sannino in Naples, after Buongiorno moved there in the 1880s. (Supporting this theory, the majority of Sanninos in Italy today are located in the Naples area, per telephone listings.)

Sannino emigrated to the U.S. in 1893, one year after Buongiorno. (With him on the boat is a man from Solofra, Francesco Cirino, age 29, laborer.)

Sannino became a naturalized American citizen in 1906, shortly before his first trip back to Italy, as was common. He also travelled to Italy in 1925. He died in New York in 1946.

Sannino was a cabinet maker (an “expert, artistic cabinet maker” according to Domenic Troisi.) In his vital records, Sannino is always identified as either a "wood worker" or "cabinet maker," working (seemingly steadily) in furniture factories in Manhattan.

My favorite record of Sannino’s connection to Buongiorno’s family is a memento he and Buongiorno made as a Christmas gift for my grandfather, Domenic Troisi, in 1916. It's a cigarette box signed by both of them and inscribed to the then 22-year-old Domenic. I am certain Sannino made the box and Buongiorno painted its decorations.

I also suspect Sannino may have made frames and stretchers for Buongiorno's easel paintings. (Some look hand- or custom-made.)

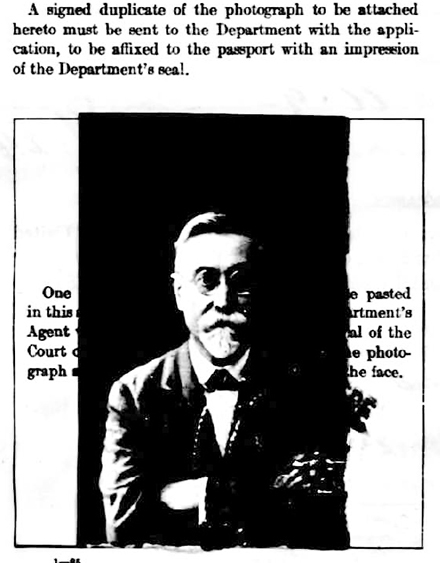

The photograph in the header of this page is of Sannino. It is from his 1925 passport application when he was 56 years old.

Felice Cuniberti

Also known as Felix CunibertiIn addition to Paquale Sannino, the 1900 U.S. Census, shows other boarders in Donatus Buongiorno’s home, including two brothers-in-law, one being Felice Cuniberti.

I have not been able to determine the familial connection of these brothers-in-law, and I suspect that is because the term was used to describe more than the husband of a sibling. If Italians extended this term to the husbands of siblings’ spouses and to the husbands of one’s spouse’s siblings, then many more potential surnames are “in play,” making it too difficult for me to trace.

Born in 1870 in Naples, Cuniberti emigrated to New York in 1895 as an already-educated professional. Among the farmers, peasants and other craftsmen on his steerage-class manifest, his “forwarding agent” job stands out (line 6.)

He became a naturalized U.S. citizen in 1901, two days before he was issued a passport for his first return trip (of several) to Italy. In 1905 he was applied for passports for his wife Clelia and two daughters, Teresa and Margherita, to emigrate to the U.S.

His continued professional employment in New York is evident from the titles and addresses in his documents: "forwarding agent" on his 1895 manifest, "Custom House Broker" in the 1900 census.

He worked at a company called Morris European and American Express Company, which he left in January 1901 to form his own company, with partners, called Merchants European Express Co. In 1901 the company was located at 24 State Street; in 1905 it was at 59 Broadway. Both addresses are in Manhattan.

My favorite record of Cuniberti is a letter he wrote to The New York Times in reply to a letter from a local crank, Samuel Conkey. Having previously weighed in with his objections to pigeon shooting and deckle-edge pages in books, Conkey moved on to heavier matters in 1906, complaining about “undesirable foreigners,” including “Italian murderes and counterfeiters.”

Felice/Felix Cuniberti's response is eloquent and controlled, despite its somewhat broken English, and it also gratifies me for another reason. It demonstrates that Donatus Buongiorno associated with intellectual thinkers who, like him (see 1908 Petition to U.S. Congress), weren't afraid to act on their principles and take public action in their new country.

Frank Caiazzo

Listed as Donatus Buongiorno's brother-in-law in the 1900 U.S. Census, I have not been able to learn anything else about Caiazzo other than that he was a laborer who emigrated from Italy in 1900, as claimed in the census. There are no Caiazzos in the birth records of Buongiorno’s home town of Solofra, so he must have married into the family from elsewhere, most likely Naples or its environs. (In Italy today, Caiazzos listed in telephone books center preponderantly around Naples.)

Do you know any of the men on this page? Perhaps you are a relative of them? If so, I would love to hear your family’s story and to see if we can fill in the gaps in my story.